Science Academy Vows to Promote Progress

|

| Geophysicist Shao Ming’an oversees the management and recovery of a sand ecosystem at an afforestation base in the Ordos Desert in Shenmu county, Shaanxi province. SUN ZIFA / CHINA NEWS SERVICE |

Highest academic institution urges members to transform China into a technological powerhouse. Zhang Zhihao reports.

In September last year, despite having serious heart disease, Shao Ming'an, a noted geophysicist and member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, asked his doctor to unclip his heart monitor and other medical equipment so he could leave the hospital temporarily.

Shao wanted to advise his new PhD students on their admission reports. After two hours interacting cheerfully with the students, Shao returned to the hospital exhausted but fulfilled. None of the students knew he was seriously ill.

"I don't fear death," said the scientist, who in 2013 taught geophysics for a week from his hospital bed so his illness would not jeopardize the progress of his class. "Scientists have to be ready to sacrifice themselves. I simply want to be as useful as possible to the country."

The 62-year-old has spent 36 years improving ecological restoration and irrigation techniques across the 640,000-square-kilometer Loess Plateau in central and northern China, one of the largest, most fragile ecosystems in the world.

He is one of many scientists from the academy, China's highest academic institute, who have dedicated their entire lives to the country. He embodies the academy's motto - "Serving the Nation through Science and Technology" - which has been upheld since it was established in 1949.

Now, the motto is becoming more prevalent within the scientific community as the nation's overreliance on key technologies from other countries is highlighted by the current trade dispute with the United States.

In April, ZTE, China's No 2 telecommunications equipment maker, was forced to suspend operations because inventories were almost exhausted after the US imposed a seven year ban on its purchase of crucial components, including computer chips, on allegations it had breached sanctions on exporting goods to Iran. The ban was lifted in July.

On May 28, during a meeting with scientific and engineering academicians, President Xi Jinping said reliance on other countries' key technologies, from high-end chips to basic software, has not fundamentally changed over the years.

Xi urged the nation's top scientists to rekindle their patriotic spirit and make greater efforts to solve key technological issues that are hampering growth.

In an address to young scientists at the July launch ceremony of the academy's first education center on patriotism, Hou Jianguo, vice-president of CAS, said, "In our nation's great time of need, we scientists must align our personnel work to help the country's development."

He advised them to inherit diligence, devotion and patriotism from their mentors and past generations of scientists, and noted that 63 percent of the 790 CAS academicians are Party members, "and they have contributed greatly to China's technological development".

"At the academy, young scientists who are also Party members are playing important roles in many fields," he said.

"But young scientists can learn much from their role models, and doing so will arm them with the spirit to shoulder the duty of turning China into a global technological powerhouse."

Li Wei, a researcher at the academy's Institute of Zoology, said whenever he has trouble at work or in life, his mind is eased by recalling the Party's history and role models.

"It is our (young scientists) duty to work for the prosperity of the people and the nation," he said. "Innovation will be our answer to the call of duty, and we will work hard to create new achievements that can live up to expectations."

|

|

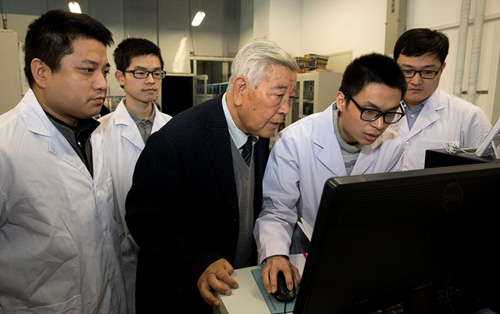

Academician Zhao Zhongxian discusses superconductive materials with his students in Beijing. JIN LIWANG / XINHUA |

Life lessons

A poem hangs in the office of Zhao Zhongxian, winner of the 2016 State Preeminent Science and Technology Award, China's highest scientific honor.

The ode - penned by Zhao's colleague Peng Huanwu, a nuclear physicist who paved the way for the development of nuclear energy in China - was written in 1987 to encourage Zhao, who was working on superconducting materials.

The latter section reads, "Returned from overseas, to research and teach, and after several generations of hard work, China's physics can finally take root."

Zhao, who was a visiting scholar at Iowa State University in 1984, said, "The poem summarizes the lives and aspirations of many noted Chinese scientists in past decades."

The 77-year-old returned to China in 1986 to help build superconductors, a key component in advanced electronic devices such as maglev trains, supercomputers and lasers.

Like Zhao, Peng relinquished tenure overseas. He returned to China in 1947 after producing seminal works on theoretical physics at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies in Ireland.

For his contribution, Peng was elected to the Royal Irish Academy in 1948, despite his absence.

"When I asked him why he returned, he said there was no special reason," Zhao said. "He just wanted to use his knowledge to help his country, which sorely needed talent like him."

In 1959, nuclear energy, rockets, satellites and semiconductors were the most popular subjects among Chinese college students.

"We were fascinated by the Soviet Union's scientific achievements, especially after it launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, in 1957," Zhao said.

About 2,500 people sat in the fields at the University of Science and Technology of China in 1959 and listened to nuclear physicist Qian Sanqiang report on scientific development, according to Zhao.

"We were thrilled by science, but also felt a strong sense of responsibility," he said. "But we soon discovered that passion is not enough, you must also have knowledge. This is only achievable through dedication and intense concentration."

Renowned mathematician Hua Luogeng was known to lose himself in deep thoughts, even during conferences. "His face always looked so serious because he was thinking about math problems all day," Zhao said. "Hua taught me by example that scientists really have to give it everything to succeed."

Zhao took the lesson to heart, and spent half a century researching high-temperature superconducting materials. In 2013, his discoveries earned him first prize at the State Natural Sciences Awards, China's highest accolade for basic research.

"Scientists often jokingly called my field'a cold stool', given how long and difficult it is to make breakthroughs," Zhao said. "But I believe that with passion and dedication, and if you sit on the cold stool long enough, it can become warm."

In addition to dedication, Zhao said that to be innovative scientists need to excel at three things: spotting anomalies; creating solutions; and drawing conclusions.

The prerequisite for these conditions is "mastery over knowledge and one's subject", he said. "Sometimes original research is not as complicated as we think; the key is to find a goal worth devoting your interest and attention to for life."

|

|

Hou Jianguo, vice president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, interacts with a graduate at a ceremony in Anhui province. XINHUA |

Model scientist

In November, Shao met with an old friend, physicist Gong Xingao, in Beijing. Both were to receive their academician's certificate for CAS. Gong held Shao's hand, laughed and said, "The mud-playing boy is here."

Shao was born into a farming family in Hunan province in 1956. "I am a farmer's kid, and have loved playing with mud since childhood, but I did not expect to actually achieve anything from it," he said.

He studied electrodynamics at college, but insisted on combining his childhood passion for geography with the rigorous discipline of physics. As a result, he became a researcher in geophysics at the academy's Institute of Soil and Water Conservation in Yangling, Shaanxi province. He has devoted his life to surveying the Loess Plateau.

The surveys usually involve traveling by foot through treacherous terrain and harsh weather to drill and collect soil samples. Shao did the job well into his 50s, often starting at 5 am and finishing after dark.

After more than three decades of research, he has collected more than 15,000 samples, covering almost the entire plateau. "Scientific research can't be impetuous, you must endure hardship and solitude, and create something beneficial to society" he said.

Shao was also indefatigable. At age 27, he narrowly escaped being electrocuted when a 380-volt cable fell on him as he erected a canopy to protect his soil samples during a rainstorm. He carried on regardless.

Early ecological restoration and irrigation efforts on the plateau proved ineffective, so Shao tried to identify the source of the problem using mathematical models and data collected from his survey.

He discovered that some parts of the plateau have higher levels of evaporation and thinner, less fertile soil, which severely limits their ability to produce crops and trees.

However, new mathematical models have allowed scientists and policymakers to craft specific measures to target certain regions, such as planting trees in the southern part of the plateau where growth capacity is relatively high, and reducing agricultural water use by half while ensuring the same harvest.

"These are all practical ways of helping China become a more beautiful country," said Ge Quansheng, director of the CAS Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research.

"Shao's work does not just belong in scientific papers and classrooms - it also touches the lives of more than 110 million people living on the Loess Plateau. He is a model scientist for the new age." (China Daily)

Contact the writer at zhangzhihao@chinadaily.com.cn

Download attachments: